This article is more than 36 months old and is now archived. This article has not been updated to reflect any changes to the law.

clearlaw

Self Managed Superannuation Funds (SMSF)s buying in-house assets: When will the ATO allow it?

The law prohibits SMSF's from owning in-house assets — but the ATO has a discretion. This article reviews the ATO's position on when it will exercise that discretion to allow an SMSF to own an asset that it might otherwise be prohibited from owning.

What is an in-house asset?

Broadly, an in-house asset of a superannuation fund is an asset of the fund that is:

- a loan to, or an investment in, a related party of the fund;

- an investment in a related trust of the fund; or

- an asset of the fund subject to a lease or a lease arrangement between a trustee of the fund and a related-party of the fund.[1]

What is not an in-house asset?

An asset is not an in-house asset of a superannuation fund in certain prescribed circumstances, including:

- when the superannuation fund has fewer than five members (which includes all SMSFs); and

- the relevant asset is 'business real property' under a written lease between the trustees of the fund and a related party.[2]

What is the limit on in-house assets for SMSFs?

The value of in-house assets that a trustee of a superannuation fund may acquire and hold is limited to 5% of the market value of the fund's total assets (Excess Amount).[3]

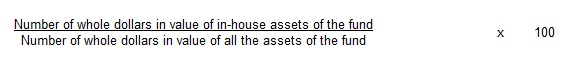

The Excess Amount is calculated using the following formula[4]:

To the extent that this area of law relates to SMSFs, it is administered by the Commissioner.

What is the Commissioner's power to make a determination (that is, his 'discretion')?

As the regulator of SMSFs under the SISA, the Commissioner has the power to determine under paragraph 71(1)(e) that a particular asset of an SMSF is not, or will not be, an in-house asset of the fund.

When will the Commissioner exercise his discretion?

The law does not provide any criteria limiting when the Commissioner may exercise the discretion. Rather, the Commissioner must exercise the discretion by reference to the legislative context in which the law appears.[5]

Broadly, the Commissioner will exercise his discretion:

- if there are circumstances that are 'unusual or out of the ordinary'; and

- if issuing the determination would not undermine the purpose for which the in-house asset rules of Part 8 were introduced.

What will the Commissioner consider?

In deciding whether to exercise his discretion, the Commissioner will consider the following:

- Circumstances out of the ordinary: the Commissioner may issue a determination under paragraph 71(1)(e) if the circumstances are in some way unusual or extenuating.

Example: After the introduction of a requirement for a registrable superannuation industry licence (in 2004), the trustees of some small superannuation funds (regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Fund (APRA)), wanted to transfer their funds to SMSFs because the trustees did not want to become licensed trustees. At the time, the issue was:

-

assets which were not in-house assets of the APRA fund due to the operation of the transitional provisions would continue to be excluded from the in-house assets of the SMSF if the APRA fund itself was to become an SMSF; but

-

if the APRA-regulated fund wished to divide assets between that fund and an SMSF, then assets transferred from the former APRA fund to the new SMSF would become in-house assets of the SMSF.

Accordingly, the in-house assets of the SMSF may have exceeded the Excess Amount. The ATO's view was that the introduction of a licensing regime was unusual or out of the ordinary — because it was outside the trustee's control. After all, when the APRA fund trustees acquired the assets which were not then in-house assets of the APRA fund, they were not in a position to foresee the introduction of the new licensing requirements under which the acquisition was made. Therefore the ATO exercised its discretion to allow the assets to be held by the fund.

-

- Scope and intent of Part 8: even if circumstances are unusual or out of the ordinary, the determination must not undermine the purpose of the in-house asset rules. These rules are designed to ensure that the investment practices of superannuation funds are consistent with the SISA objective of limiting the risks associated with investment in related parties.

When won't the Commissioner exercise his discretion?

Examples of when the Commissioner won't exercise the discretion under paragraph 71(1)(e) include:

Fluctuations in economic conditions. Large changes in the value of an investment due to fluctuations in economic conditions won't justify the discretion. It would be contrary to the object of the in-house asset rules for in-house assets with a value above the Excess Amount to be permitted merely because of a substantial increase in the value of the in-house asset, or a substantial decline in assets other than the in-house asset.

- Reliance on due care and diligence by a professional: Such as the advice of an accountant in relation to the books and records of the SMSF.

Example The Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) has held that a trustee who relied on advice from its accountant in relation to loans of the SMSF was still responsible for informing itself of the true factual situation of the fund at the time it signed the fund's tax return. The AAT considered that relying on accountants (and presumably on any adviser), even if they have done all they could to inform the trustee of the situation, does not constitute a special circumstance.[6]

- If the trustee is unaware of the requirements of the in-house assets rules: Such as failing to identify a unit trust as a related party of the fund before making an investment. This is not considered a circumstance beyond the trustee's control.

How does this apply to a particular SMSF?

A determination made by the Commissioner under paragraph 71(1)(e) is issued to a specific SMSF in relation to its particular assets. Accordingly, a determination made in respect of another SMSF cannot be relied on even if your, or your client's, situation is arguably the same as that other SMSF.

If you want clarity as to whether an asset of a particular SMSF is an in-house asset, then you should seek a determination by the Commissioner.

Earlier ClearLaw articles on in-house assets:

- October 2007: The ATO's View on the Meaning of "In-House Assets"- New Draft Determination | ClearLaw Legal Bulletin | Australia

- October 2006: In-house assets: is your SMSF ready — or preparing — for June 2009? (Yes, that's 2009) | ClearLaw Legal Bulletin | Australia

Any questions?

For more information, please contact Maddocks (03) 9288 0555 and ask for a member of the Cleardocs Help Desk. They will put you in contact with the relevant Tax & Revenue lawyer in Melbourne or Sydney.

More Cleardocs information on SMSFs

Read

about the Cleardocs Superannuation Trust (SMSF)Order SMSF related document packages

Set up an SMSF

Update an SMSF deed

Set up an SMSF pension

Arrange SMSF borrowing lending docs:

Set up an SMSF corporate trustee

SMSF Death Benefit Nomination — binding or non-binding

An SMSF Death Benefit Agreement — binding and permanent

Download checklist

Download a checklist of the information you need to order a document package.

[1] As set out in section 71(1) of Part 8 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SISA).

[2] Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994, 13.22B(2) and 13.22C(2).

[3] Part 8 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (SISA)

[4] SISA section 82(3).

[5] Paragraph 71(1)(e)

[6] AAT Case 9537 (1994) 28 ATR 1220.

Lawyer in Profile

Associate

+61 3 9258 3247

stephen.dyason@maddocks.com.au

Qualifications: LLB, Deakin University

Stephen is a member of Maddocks Commercial team. He is a corporate and commercial lawyer, who assists clients across a diverse range of industries including financial services, consumer markets and manufacturing in a wide variety of legal matters.

His experience includes:

- mergers and acquisitions,

- corporate reorganisations, and

- general commercial law work.

He focusses on drafting, advising on and negotiating contracts, transactions and agreements for clients and also assists with providing general corporate advice.

Read Our Latest Articles

Superannuation

Federal Super Tax Backflip: Understanding the revised superannuation reforms

Superannuation

Proposed Superannuation Tax Increase: Extra 15% tax, where Funds have $3 Millions

customer support

legal advice

-

The legal information and commentary on this site is general only. Documents ordered through Cleardocs affect the user's legal rights and liabilities. To assess their suitability for the user, legal accounting and financial advice must be obtained.